Area characterisation:

About Hamburg:

Hamburg is the second-largest city in Germany after Berlin, as well as the overall 8th-largest city and largest non-capital city within the European Union with a population of over 1.9 million. Hamburg's urban area has a population of around 2.5 million and is part of the Hamburg Metropolitan Region, which has a population of over 5.1 million people in total.

The Green Network around half of the city’s area includes green spaces and recreational areas consisting of two green rings and twelve landscape axes. The first ring is around 1 kilometer from the town hall on the old wall ring connecting Elbe and Alster in an arc and the second ring circles the city for around 100 kilometers and connects parks and cultural areas.

The crowded city center is framed by the first Green Ring on the historic Wallring, while the second Green Ring, which is 100 kilometers long, provides a chance to explore Hamburg's varied green areas. Located eight to ten km from the town hall, the 2nd Green Ring provides a variety of impressions as it encircles the central city. It is a huge attraction to hiking enthusiasts, with multiple natural reserves on the way including Boberger Niederung, the Allermöher Wiesen and the Eppendorfer Moor.

Objective:

The CLEVER Cities project identified the primary planning goals for Neugraben-Fischbek district located in the South-West of the city of Hamburg was to: (a) creating a connective ‘Green Corridor’ to link a system of NbS interventions; (b) establishing horizontal greenery through the construction of green roofs on existing buildings; and (c) address the topic of environmental education and connect the youth with nature.

Hamburg has aimed at addressing the following challenges, including:

-

Increase biodiversity and nature in the city: To address this, the city connected different NbS interventions as a part of CLEVER Cities through the CLEVER corridor. The idea was to connect the city to nature with an emphasis on nature within the city. It has one part of the East-West walking/cycling path as a pilot project for redesigning the rest of the path. To increase biodiversity and overcome gaps in-between surrounding natural heritages, Nature-based Solutions were implemented along the corridor, to narrate the CLEVER story along the path a guiding tool will be developed.

-

Developing and implementing Green Roofs and Green Facades along the CLEVER corridor and within the project area in cooperation with the public and private stakeholders. With the focus on creating green spaces that not only enhance recreation activities and attractiveness of the neighborhood, but also create a living environment for animals, insects and plants, while emphasizing on improving the urban climate and increasing the local rain retention capacity. The main objective was to modernize the existing roofs and walls in order to use them as roof gardens, recreation areas, or habitats. The mission was to test new construction techniques and materials, while research will also monitor effects on rainwater retention and wellbeing due to expected positive effects on local climate.

-

Designing and implementing multifunctional green spaces: The three schools in the Neugraben-Fischbek area, Stadtteilschule Fischbek-Falkenberg, Schule Ohrnsweg and Grundschule Neugraben were renewed. The school students are an important part of disseminating environmental and sustainability education to their family and friends as the school gardens include not only community gardens but also green roofs and rainwater management.

Images

Potential impacts/benefits:

Stakeholder Participation:

In order to jointly design and carry out urban regeneration interventions, stakeholders in the CLEVER Cities project engage in cooperative engagement activities known as co-creation. When it comes to co-design and co-implementation processes, stakeholder analysis is essential to comprehending their traits, behaviours, and resources.

Based on their kind, name, function, resources, and degree of involvement, stakeholders are categorized by the stakeholder analysis. Groups include citizens, non-governmental organizations, the private sector, research and academia, and governmental bodies. There are different types of roles: active (like steering groups) and passive (like landowners). Financial, cognitive, relational, and decision-making power are all examples of resources.

Each Collaborative Action Lab (CAL) consists of:

-

CAL1 encompasses a wide range of stakeholders, including citizens, NGOs, the public and private sectors, and academic institutions, all of whom contribute different resources and degrees of engagement to form the foundation of co-creation.

-

Stakeholders with varying roles, interests, and resources are involved in CAL2, which focuses on rainwater management and vertical greenery.

-

Stakeholders from three schools, including teachers, parents' unions, students, and local foundations, are the main participants in CAL3. Beyond the initial school garden redesign projects, other parties became involved, including private contractors, a variety of educational institutions, and open establishments for children and youth. By voluntary collaboration with neighbourhood organizations and locals, this expansion seeks to spread environmental education outside of school walls.

Actions:

Actions

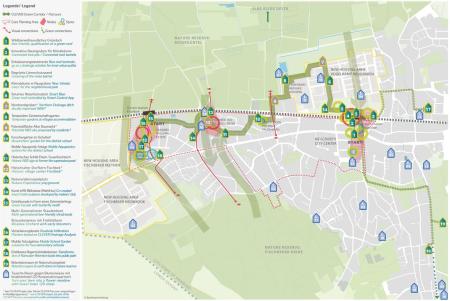

The CLEVER Cities project has established three primary CALs in the south-west part of Hamburg which covers an area of ca. 220 76ha width approx. CAL1 is dedicated to the Green Corridor, CAL2 focuses on Green Roofs and Facades in the existing quarters in Neugraben-Fischbek, and CAL3 is centered around the schoolyards in 3 different schools in the project area. All three CALs have performed their tasks efficiently in spite of a number of difficulties, such as political and bureaucratic roadblocks, pandemic-related limitations, and unanticipated limitations in the building industry. The co-creation, co-design, co-implementation, and monitoring pathways outlined by CLEVER Cities were adhered to by each CAL.

-

CAL 1: Green Corridor

Urban Greening Projects: CAL1 includes a range of ‘stepping stones'-style urban greening initiatives.

Vision of the Green Corridor: The connective 'Green Corridor' in NF creates spot-like interventions that connect two nature conservation areas, Moorgürtel in the north and Fischbeker Heide in the south.

Enhancement of Biodiversity: By putting policies in place such as qualifying green spaces, orchard meadows, and diverse flower meadows, the green interventions help to increase the biodiversity of urban areas and promote biodiversity in the region.

Social impacts: These interventions enhanced biodiversity, fostered the rebirth and unity of the Fischbek and Neugraben neighborhoods.

Place-Specific Interventions: Trail connections with wild bee hotels, nesting aids, temporary gardens with refugees, bee-friendly shrub gardens for seniors are the various interventions that involved various groups in community building and co-creation.

Overall, CAL1 connects nature conservation areas and promotes community cohesion and engagement in urban areas through the development of green interventions that improve biodiversity and have social benefits.

Key Aspects emphasizing diverse interventions and stimuli:

-

Diverse Interventions and Objectives:

-

NbS with small-scale site-specific objectives are put into place throughout the CLEVER Corridor with an emphasis on improving biodiversity, establishing green connections, and offering livable spaces to locals.

-

Through partnerships, such as the provision of climate-resilient tree species by local foundations and long-term visions by the local initiative WerkHus, additional resources are facilitated.

-

Engagement and Co-Design Process:

-

Actor motivation and engagement (e.g., voluntary sponsorship, gardening group formation) are critical to the co-design process's success.

-

Following the pandemic, attempts were made to activate Urban Intervention Points (UIPs), which brought locals together through support group meetings, district council festivals, citizen councils, and larger events.

-

Core Approaches and Co-design:

In order to include a variety of stakeholders, spark community activity, the co-design process in CAL1 made use of a number of formats and methods:

-

Workshops: A tool for defining project milestones, bringing together a variety of stakeholders, and talking about design solutions. In particular, vulnerable groups.

-

On-site Walks/Tours: By setting up outdoor co-design activities in recognisable settings, stakeholders gain a better understanding of projects and forge local connections that aided in project development.

-

Modeling and hands-on design: Getting kids involved in making real designs helped them grasp the impact of the project and develop their creativity.

-

Online Tools: Participation was made possible through digital platforms, though the success of each approach varied according to the project and level of audience involvement.

-

Social media platforms: They educated and engaged the public, their working relied on how relevant the content was to the users.

-

Neighborhood Events: Crucial for project advancement, recognising stakeholder input, and commemorating successes. These community-wide events involved a variety of groups and ranged from co-design to implementation and inauguration.

-

Bilateral and Multilateral Exchanges: Timely exchanges and decision-making processes by regular partner meetings and phone calls.

-

CAL 2: Green Roofs / Green Facades

-

Goal and Vision:

-

By adding green roofs to already-existing structures, CAL2 adds more horizontal greenery.

-

This being in line with the Hamburg Green Roof strategy increases the amount of money available for smaller-scale roof greening projects, such as those the size of carports.

-

CAL2 links existing quarters with newly constructed residential areas in Neugraben-Fischbek, facilitated the creation of additional public green spaces for leisure and recreation, and integrated these spaces into already-existing green networks.

-

Objectives and Challenges:

-

Green roofs reduce the impact of stormwater runoff on nearby infrastructure and to lessen the local heat island effect.

-

Nevertheless, despite all of the advantages, individual building owners and housing companies initially showed very little interest in these green initiatives.

-

Expansion to Vertical Greenery:

-

Owing to the lack of interest in green roofs, CAL2 covers green noise barriers and façades projects. Nevertheless, stakeholders' interest in these vertical gardening initiatives are minimal

-

Shift to Rain-/Stormwater Management:

-

CAL2 focuses on rain- and stormwater management projects in order to address location-specific drainage problems, creating a Drainage Analysis for Heavy Rainfall for Neugraben-Fischbek.

-

Implementation of NbS Solutions:

-

Two NbS solutions found in the Drainage Analysis are put into practise with CLEVER's assistance.

-

A Blue-Green Roof managed by a smart app and other cutting-edge stormwater-related pilot or research projects are included in CAL2.

Co-design processes in CAL2:

-

Less complex co-design compared to CAL1:

-

CAL2's co-design processes have lower participation levels and possibly less holistic approaches than CAL1, in particular the rainwater management solutions are more technical, necessitating expert knowledge and less community involvement.

-

Challenges in Establishing UIP and focus area changes:

-

The shift in CAL2's focus areas from green roofs to green facades and then rainwater management projects establishes the Urban Intervention Point (UIP) at the CAL level.

-

Diverse Methods and Approaches for Co-design:

-

Diverse techniques customized to each NbS solution are employed in co-design processes including - reconsidering co-design procedures for engineering construction projects with local stakeholders, collaborating with the Triple Helix (academia, planning offices, and public administration).

-

Challenges and Adaptive Approaches:

-

Increased improvisation and ad hoc co-design processes resulted from obstacles like project kick-start delays, uncertainty surrounding project realization, and time constraints.

-

Variations in Co-design Approaches:

-

Information letters and post-implementation feedback forms are the main means of obtaining citizen engagement.

-

To observe and collect feedback on tree growth after implementation, digital tools such as QR codes are set.

-

CAL 3: Schoolyards

CAL3 reconnects the younger generation with nature and to concentrate on environmental education, so the school yards for Ohrnsweg, Neugraben Elementary School, and Fischbek-Falkenberg District School were redesigned. The plan is to include school garden solutions for hands-on instruction in food production, gardening, and sustainability. The advantages of the initiative encourage physical activity and a healthier lifestyle while fostering environmental stewardship, work ethics, and a sense of responsibility.

Objectives, Challenges and collaborative efforts taken by CAL3 to foster environmental education and engagement with nature among the young generation:

-

Mobile Raised Garden Solutions: Implemented due to the changing timeline for school yard restructuring at the elementary schools; involve active participation from pupils, parents, teachers, and university students.

-

Challenges Due to Pandemic: Closure of schools highlighted the need for alternative environmental education sources beyond school settings.

-

Partnership with Loki-Schmidt Foundation: Collaboration to find 20 local cooperation partners, focusing on youth centres, kindergartens, and other educational institutions.

-

Initiatives Undertaken: Transformation of lawn areas into flower meadows, installation of custom bee hotels to promote urban biodiversity.

-

Educational Offerings: Customized workshops, community monitoring, a photo competition, colorful information material, and 'nature walks' aiming to provide valuable environmental education and experiences to the targeted audience of CAL3.

Co-design methods in CAL3:

The co-design strategies in CAL3 prioritize collaboration with educational institutions, youth, and schools; Including swapping the monoculture lawn into the flower meadow' project. There were many challenges faced during the pandemic by the co-creation methods.

Despite its limitations, the "Researchers' Garden" model at Fischbek-Falkenberg allows for a streamlined co-design process because it was developed before the pandemic. It emphasizes a holistic approach, fostering learning on all sides, and involves teachers, experts, and CLEVER partners.

Ohrnsweg and Neugraben also experimented with mobile school gardens. A bottom-up strategy that involves local carpenters and workshops to boost economic support and local engagement.

Apart from that, the Loki Schmidt Foundation's 'Swap your monoculture lawn to the flower meadow with insect hotel' project involved schools, homeowners, and a 'Citizen Science' programme promotes awareness to protect biodiversity.

Despite obstacles, the process demonstrates a bottom-up, stakeholder-driven methodology to achieve design solutions while also promoting environmental education and awareness.

Transferability of result:

Co-design tools employed across all CALs:

Several tools are used in addition to different co-design techniques, to facilitate the co-creation process in Hamburg:

DIPAS Tool: An electronic integrated participation system that lets people participate in the planning process. It helps develop the CLEVER Parcours, design a Nature Experience Playground, and create climate trees and benches in Neugraben-Fischbek. Enhancements to accessibility encourage a wider range of citizens to participate.

CLEVERmobil² Communication Tools: A cargo bike serving as a moving platform for community members, enables activities such as school picnics and mobile cinema. It offers a modular design for multifunctional use.

Planning Tools: "Drainage analysis for heavy rainfall in Neugraben-Fischbek" is a computer model that indicates areas that are vulnerable to flooding and suggests using nature-based solutions (NbS) to control runoff. Retention areas and roadside infiltration planters are examples of solutions that have been put into practise.

WerkHus: A bottom-up initiative that combines public space design with a gathering place for neighbourhood organizations to promote community involvement. designed bug hotels as noticeable landmarks with the intention of establishing a work area, coffee shop, workshops, and instructional programmes.

These resources highlight inclusive participation, citizen engagement, and workable solutions while showcasing the variety of strategies employed to encourage co-creation and apply nature-based solutions in urban environments.

Co-implementation challenges and general conclusions for all CALs:

The challenges associated with co-implementation processes in Hamburg are numerous and can be summed up for all CALs as follows:

-

To support and mentor bottom-up initiatives/clubs that can co-implement NbS solutions, enormous human and temporal resources are required.

-

Co-implementation and co-creation are not standard operating procedures for various district departments in the absence of CLEVER, a tool that could effectively bridge the gap between the ideas of the driven local actor groups and the district administration's process for carrying out its work. It can be attributed to a number of factors, such as a lack of personnel resources, experience, and a policy framework.

-

Due to the bureaucratic procedures (e.g., explosive ordnance disposal, special use permit requirement), local citizens are reluctant to actively drive co-creation processes and plan co-implementation activities. Their inability to understand the required administrative processes or their desire to assume even minimal responsibilities when co-implementing the solutions prevent them from moving forward.

-

There is still a problem with insurance and liability when working with laymen to implement solutions. The businesses that support these co-implementation procedures frequently forego providing post-implementation care if the work is not completed by specialists, adding to the costs incurred by the "project owner" (a problematic entity that could be a local government, a group of residents, or a public administration), particularly when it comes to setting up the co-management plan.

-

The size of the private properties with gardens and the built environment's structure in Neugraben-Fischbek (which is close to nature sanctuaries) may be viewed as one of the negative triggers for the low levels of self-initiative and participation in co-managing or co-implementing NBSs in the public domain.

Pillars in order to overcome the challenges:

-

Involve some of the participants who were already involved in the co-design process. Over time, the amount of facilitation required may decrease as ownership grows as a result of ongoing participation.

-

Involve as many diverse stakeholders as you can to foster a sense of community within the jointly created areas that are not part of their private properties.

-

Make an NbS/CLEVER identity that is shared (like CLEVER Parcours) - In addition to preventing vandalism, involvement of a wide range of actors may also help dispel misconceptions about the difficulty of the co-management tasks required to uphold sustainable NbS practices.

-

By creating procedures and simple means of replication for landscape architecture and planning offices, gardener companies, and public administrations, the new demand for co-creatively developed districts and spaces is created.

-

Set an exemplary example and disseminate the best practices via the already-existing channels of communication (e.g., the CLEVER signage system that links to the Hamburg webpage and offers more details on the jointly-created NbS solutions).

Lessons learnt:

Challenges & Lessons learned:

-

Challenges:

The CLEVER Cities project encountered several challenges in the co-design phase, hindering sustained stakeholder engagement and effective project ownership. Common issues across the three Collaborative Action Labs (CALs) included:

-

Stakeholder Disengagement: Recurrent participation of stakeholder groups was relatively low, especially during the pandemic. Time constraints, shifting priorities, and competing engagement structures contributed to limited involvement. This required tailored communication strategies and diverse engagement formats to address specific stakeholder needs.

-

Plurality of Interventions: Numerous interventions led to overall stakeholder disengagement rather than continuous involvement. To address this, the project employed various methods and communication tools, blending digital and analogue approaches, and establishing new communication channels.

-

Ad-hoc vs. Sustainable Groups: Establishing self-driven groups (UIPs) to ensure long-term project ownership was challenging. Long-term commitments such as maintenance responsibilities hindered participants from transitioning from interest to sustained action. While bottom-up initiatives were supported, co-management was rarely addressed in the co-design phase.

-

Resource Scarcity: Insufficient incentives and time/personnel resources for sustainable UIP groups posed challenges. Voluntary participation often lacked continuous interest and engagement, leading to project components being left unattended. Dedicated local coordinators with guaranteed financial support proved crucial for sustained engagement.

To counter these challenges, the CLEVER Cities project implemented tailored communication strategies, diversified engagement formats, and supported bottom-up initiatives. However, sustaining stakeholder engagement and fostering long-term project ownership remained ongoing challenges, particularly in balancing stakeholder commitments and ensuring adequate resources for continuous involvement.

-

Lessons learned:

An extensive summary of the procedures involved in implementing Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) across the three Collaborative Action Labs (CALs) of the CLEVER Cities project was given in the Hamburg implementations report. It described the co-design, co-implementation, and co-management procedures, emphasizing the methods, challenges, and opportunities for improvement as well as the involved parties. After considering the lessons learned, a number of crucial suggestions for the effective co-implementation of NbS in underprivileged communities were found.

In order to promote ownership, lessen vandalism, and facilitate co-creation efforts, the report placed a strong emphasis on ongoing stakeholder engagement throughout all phases. It was determined that effective monitoring, maintenance, and replication potential of NbS depend on diverse stakeholder engagement, especially when it comes to end users.

Furthermore, in order to encourage demand for more co-creation approaches in urban regeneration, the benefits of co-implementation were emphasized to a larger audience. Key factors for a successful co-implementation were determined to be: a sufficient distribution of human and temporal resources; easily navigable bureaucratic processes; utilizing pre-existing local stakeholder networks; and attending to insurance and liability issues.

By providing insightful information for future projects and public policies, the report concluded that the NbS implementations in Hamburg were successfully completed. Refining NbS and co-creation practices for standard work streams and policies will benefit from ongoing observation of post-implementation developments and lessons learned from UIPs established during interventions.

Contacts:

Martin Krekeler, Project Coordinator, CLEVER Cities

martin.krekeler@sk.hamburg.de

NBS goals:

- Enhancing sustainable urbanization

- Restoring ecosystems and their functions

- Developing climate change mitigation

- Developing climate change adaptation

- Improving risk management and resilience

- Urban regeneration through nature-based solutions

- Nature-based solutions for improving well-being in urban areas

NBS benefits:

- Developing climate change adaptation; improving risk management and resilience

- Flood peak reduction

- Increase infiltration / Water storage

- Reduce flood risk

- Reduce run-off

- Developing climate change mitigation

- More energy efficient buildings

- Reduction of energy in the production of new buildings and building materials

- Restoring ecosystems and their functions

- Greater ecological connectivity across urban regenerated sites

- Improve connectivity and functionality of green and blue infrastructures

- Increase achievements of biodiversity targets

- Increase Biodiversity

- Increase quality and quantity of green and blue infrastructures

- Enhancing sustainable urbanisation

- Improve air quality

- Increase accessibility to green open spaces

- Increase amount of green open spaces for residents

- Increase awareness of NBS solution & their effectiveness and co benefits

- Increase communities’ sense of ownership

- Increase population & infrastructures protected by NBS

- Increase social interaction

- Increase stakeholder awareness & knowledge about NBS

- Increase well-being

- Increase willingness to invest in NBS

- Provision of health benefits

- Reduce costs for water treatments

- Social inclusion

- Social learning about location & importance of NBS